Gdańsk in English, or on the conundrums of (not) translating proper names

Deciding whether to translate proper names or leave them in their original form can often become a major headache for a translator. Both strategies have as many ardent opponents as staunch supporters. In the end, it’s up to the translators themselves, as they are responsible for giving shape to a reality of the localised text. Of all the different types of proper names, it’s the anthroponyms (first names, surnames, nicknames etc.) and toponyms (geographical or place names) that raise the most doubts. Which of these should be localised, and which should be left as they are, in hope that a foreign word will not perplex the audience?

Translating a proper name – what is the best approach?

In every case of translating one word into another, it’s always the language itself that plays the greatest role, although things like cultural familiarity, political relations between countries, traditions to be followed or deviated from also need to be considered. All these elements take part in shaping the world we see and the linguistic reality around us. Let’s take a closer look at Polish translations of Lucy Maud Montgomery’s cult novel – Anne of Green Gables, known to successive generations of readers in Poland as Ania z Zielonego Wzgórza. This has changed with the publication of the 2022 edition under the title Anne z Zielonych Szczytów, with a brand new translation by Anna Bańkowska. Here, the „refurbished’ main character keeps her name unchanged, while ‘Green Gables’ become Zielone Szczyty, correctly referencing the painted top parts of the walls at the end of the ridged roof in a place inhabited by legal guardians of the titular heroine. Gone is the picturesque ‘Green Hill’ from previous translations. How the translator herself justifies her decision to make these fundamental changes in the text?

This shows that nowadays domestication strategy is often shied away from, and the best proof of that would be the names of British sovereigns – why do the Poles say królowa Elżbieta and król Karol when alluding to queen Elisabeth and king Charles, but always mention prince Harry or William?

A brief history of one city’s name – Gdańsk

Let’s look into the written history of Gdańsk, which dates back to the times of bishop Adalbert of Prague, who in April 997 went on a missionary quest to the northern lands of today’s Poland. He is the historical figure connected with the first Latinised record of the name of the city of Gdańsk – urbs Gyddanyzc – which appears in Life of Saint Adalbert, Bishop of Prague and Martyr, a hagiographical work written by John Canaparius between the 10th and 11th century. In other Medieval manuscripts you can find different names like Gyddanyze, Guddanizc, Gidanic or Gydanik, with different phonetic spelling, most probably due to a mispronunciation of the schwa vowel.

In German texts from the beginning of the 13th century, names such as Danzk, Danczk and Dantzk appear – in order to simplify the pronunciation, the consonantal cluster gd was replaced with the letter d – until finally a standardisation took place and Danzig became the official German name. Nowadays, this name raises a lot of controversy, mainly because of the troubled Polish–German historical relationship, and because of the Germanisation policies forced on the Poles in the ages before.

Gdańsk outside of Poland – Gdansk, Danzig or just Gdańsk?

Most German-speaking people use the name ‘Danzig’, when referring to Gdańsk. This should not be in any way treated as a lack of respect for Polish history, but rather as an exonym, which basically means a foreign geographical name adapted to one’s own language. And by now, the name Danzig is deeply rooted in German language. One can make a similar case for Italian and French, where Gdańsk is translated as Danzica and Dantzick respectively. And what about English?

In the language of the great bard the term ‘Danzig’ is usually used in historical contexts. When talking or writing about modern times, you should definitely use the name ‘Gdańsk’, or – in the case of people without access to a keyboard with Polish characters – the version without diacritic signs, ‘Gdansk’. An interesting thing is that if you enter the phrase ‘Danzig tourist attractions’ into Google Search, it will automatically suggest entries with Polish version of the city’s name.

Not Turkey but Türkiye

In June 2022, United Nations acceded to a request made by the president of Türkiye to refer to the country he’s a representative of by the name Türkiye instead of the Westernised Turkey. One of the reasons behind this change was the unfortunate connotation with a… bird.

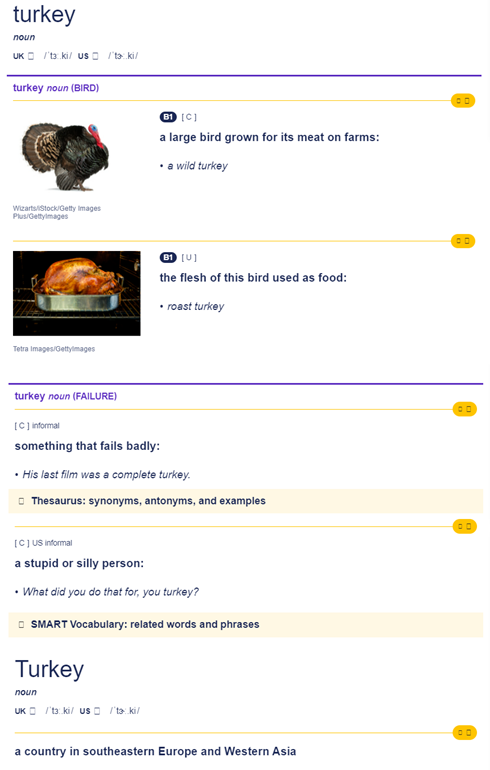

One of the most renowned dictionaries of English, the Cambridge Dictionary, lists five definitions of the word ‘turkey’.

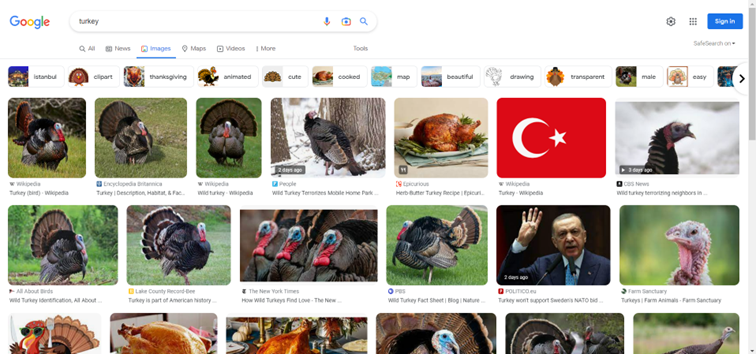

As evidenced by the above screenshot, not until the fifth place on the list will you find the information that this word can also refer to a country well-known for its ‘Turkish delight’ delicacy, patterned carpets and breath-taking landscapes. Apart from the definition of a large, flightless, domesticated bird, the dictionary also points to two other colloquial meanings of the word: ‘something that fails badly’, and ‘a stupid or silly person’. What is more, when you look for the word ‘turkey’ in Google, you will be presented with a myriad of pictures, but only 2 out of 19 have anything to do with the Middle Eastern country.

In order to avoid negative connotations and support local tourism, the people responsible for building the international image of Türkiye focused on rebranding. The goal of the ‘Hello Türkiye’ marketing campaign was to show what this land of lion’s milk can offer tourists. One of the means to accomplish this goal was to mark exported goods as ‘Made in Türkiye’.

General rules of geographical nomenclature in Poland

Translating geographical names is a complex subject that has as many rules as exceptions to them. To make it easier for everybody, especially for specialists and linguists dealing with various Polish content, in 1973, the Commission on Standardization of Geographical Names Outside the Republic of Poland (KSNG) was formed. The Commission is responsible for establishing Polish exonyms, which are listed in a publication titled Official list of Polish geographical names of the world. In the case of Polish certified translations of vital records, KSNG sets out three general rules:

- If a Polish name for a given municipality exists, it should be used in official documents of every kind. So, instead of the French name ‘Nice’ you would have to use the Polonised version – ‘Nicea.’

- If a Polish name for a given municipality does not exist, the original wording should be used along with any diacritic signs (e.g. Cancún, Hradec Králové, Düsseldorf).

- If a Polish name for a given municipality does not exist, and the original name uses non-Latin script, it has to be transliterated in accordance with transliteration guidance set out by the Commission (e.g. Κέρκυρα → Kerkyra).

Summary

Translating proper names usually involves facing quite a few dilemmas. Fortunately, you’re not left alone when dealing with them, and you may utilise different helpful strategies devised by leading experts from the field of translation studies. Any professional translator has to bear in mind that every choice they make – whether they opt for domestication or foreignisation – will have specific consequences and may impact the way culture is shaped. Although the rules of translating geographical names are somewhat more rigid than in the case of people’s names and nicknames, nobody can say for sure how many significant changes are in store for us.

Leave a Reply